UNRWA: Current Aid to Gaza Insufficient to Meet Daily Needs

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Pal...

Severe Collapse in the Health System in Southern Gaza and Critical Blood Unit Shortage Threatens the Lives of the Injured

The spokesperson for the Ministry of Health in Gaz...

30 Martyrs and 150 Injured in a New Massacre by the Occupation in the Mawasi Area of Rafah

At least 30 Palestinians were martyred and 150 oth...

Dr. Hamdi Al-Najjar Martyred After Succumbing to His Injuries, Joining His Nine Children in an Israeli Airstrike

Dr. Hamdi Al-Najjar Martyred After Succumbing to H...

Zaqout: Gaza Has Become a Place of Death and Famine Has Reached 100%

Dr. Bassam Zaqout, Director of Medical Relief in s...

Israel Releases 10 Palestinian Detainees from Gaza — Names Revealed

Israeli occupation forces released 10 Palestinian...

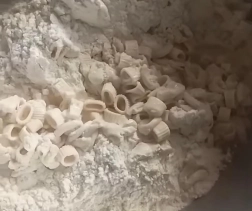

Gaza Women Turn Pasta into Flour: When Survival Becomes an Act of Innovation

In Gaza, pasta is no longer just a quick meal—it h...

Amnesty International Urges Serious Action to Stop Genocide and Starvation in Gaza

Amnesty International has called on all internatio...

Last News

New

- 2025-06-01 37 martyrs and 136 injuries in the past 24 hours in the Gaza Strip.

- 2025-06-01 Within 24 Hours... Israeli Airstrikes Destroy 6 Buildings Containing Over 100 Apartments in Gaza

- 2025-06-01 UNRWA: Current Aid to Gaza Insufficient to Meet Daily Needs

- 2025-06-01 Severe Collapse in the Health System in Southern Gaza and Critical Blood Unit Shortage Threatens the Lives of the Injured

- 2025-06-01 30 Martyrs and 150 Injured in a New Massacre by the Occupation in the Mawasi Area of Rafah